Fighting For Mobile Real Estate

The other day I wrote about the unbundling of web services. That's where an aggregator comes along and adds value by pulling lots of different services into one place -- Craigslist and Facebook are good examples. As these companies become successful, competitors come in and bite off little pieces of their service and build slick apps that do one thing really, really well. StubHub and AirBnB are good examples of apps that are 'unbundling' Craigslist.

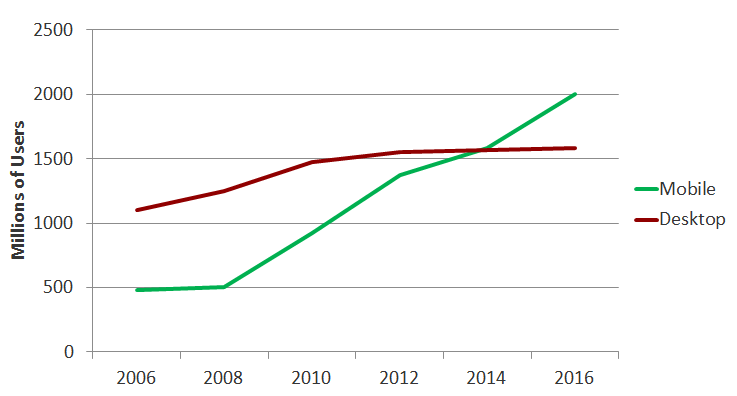

With this in mind, I came across this chart noting that later this year mobile internet usage is going to exceed desktop usage.

As mobile usage overtakes desktop usage, specialized apps that do one thing really well are going to be more and more important.

As we know, the challenge with a mobile app is that they're very limited in what they can do. You can't do as much on an app as you can do on the desktop. So as mobile becomes a bigger part of our lives I think we'll see more and more of this unbundling.

But I think we'll also see more and more bundling of retailers and merchants. That is, we're not going to download multiple grocery store apps or multiple clothing store apps or multiple travel apps.

Using myself as an example, I travel a lot. I book with 5 different airlines and probably 6 different hotel chains. As we move towards more and more mobile usage, am I going to download 11 apps? Of course not – I’m going to download one -- Expedia.

The interesting paradox with mobile is that while it will certainly continue to force innovation and specialized, "unbundled" web services, it will also drive lots of "bundled" retailer and merchant applications. Consumers will increasingly demand (and need) less and less clutter on their screens.

In short, the apps that will win the fight for real estate on our home screens will be those that serve a very narrow function very effectively (buying a plane ticket) while at the same time offering the broadest variety of options (tickets from every carrier).