Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy outlined the rationale behind their Department of Government Efficiency project (DOGE) in the Wall Street Journal last week. DOGE is intended to serve as an advisory board to streamline the U.S. federal government and reduce inefficiencies, particularly within three-letter agencies like HHS, EPA, FTC, DOD, etc. While the idea is controversial, it’s also hard not to like. No doubt government isn’t as efficient as it could be, and with the exploding federal deficit, cost reduction sounds like a nice idea. However, it’s worth noting that several presidents have tried similar initiatives in the past with limited success.

What makes this particular effort interesting, though, is its focus on reducing the thousands of regulations federal agencies have implemented over the years. The idea is that fewer regulations would mean reduced headcount to enforce those regulations and taxpayer savings. Many Americans may not realize that unelected federal agency staff write thousands of rules annually governing how businesses across the country operate.

These rules, while rooted in laws passed by Congress, are written and enforced by the agencies themselves. For example, Congress might pass a law like the Safe Drinking Water Act, and the EPA would then draft and enforce specific rules regarding contaminants, pollutant limits, and reporting requirements. This structure makes sense because Congress doesn’t have the bandwidth to dive into the details of implementing every law.

Critics argue that these agencies have amassed too much power, often acting on their own priorities rather than staying accountable to the public.

Musk and Ramaswamy wrote in their piece:

“Our nation was founded on the basic idea that the people we elect run the government. That isn’t how America functions today. Most legal edicts aren’t laws enacted by Congress but “rules and regulations” promulgated by unelected bureaucrats—tens of thousands of them each year. Most government enforcement decisions and discretionary expenditures aren’t made by the democratically elected president or even his political appointees but by millions of unelected, unappointed civil servants within government agencies who view themselves as immune from firing thanks to civil-service protections.

This is antidemocratic and antithetical to the Founders’ vision. It imposes massive direct and indirect costs on taxpayers. Thankfully, we have a historic opportunity to solve the problem.”

Government agencies, like most organizations, grow in size and scope over time. It’s human nature to want to do more with more influence, more budget, and more people. Rarely do people within these organizations prioritize limiting their scope or shrinking their footprint. It’s just not in our nature.

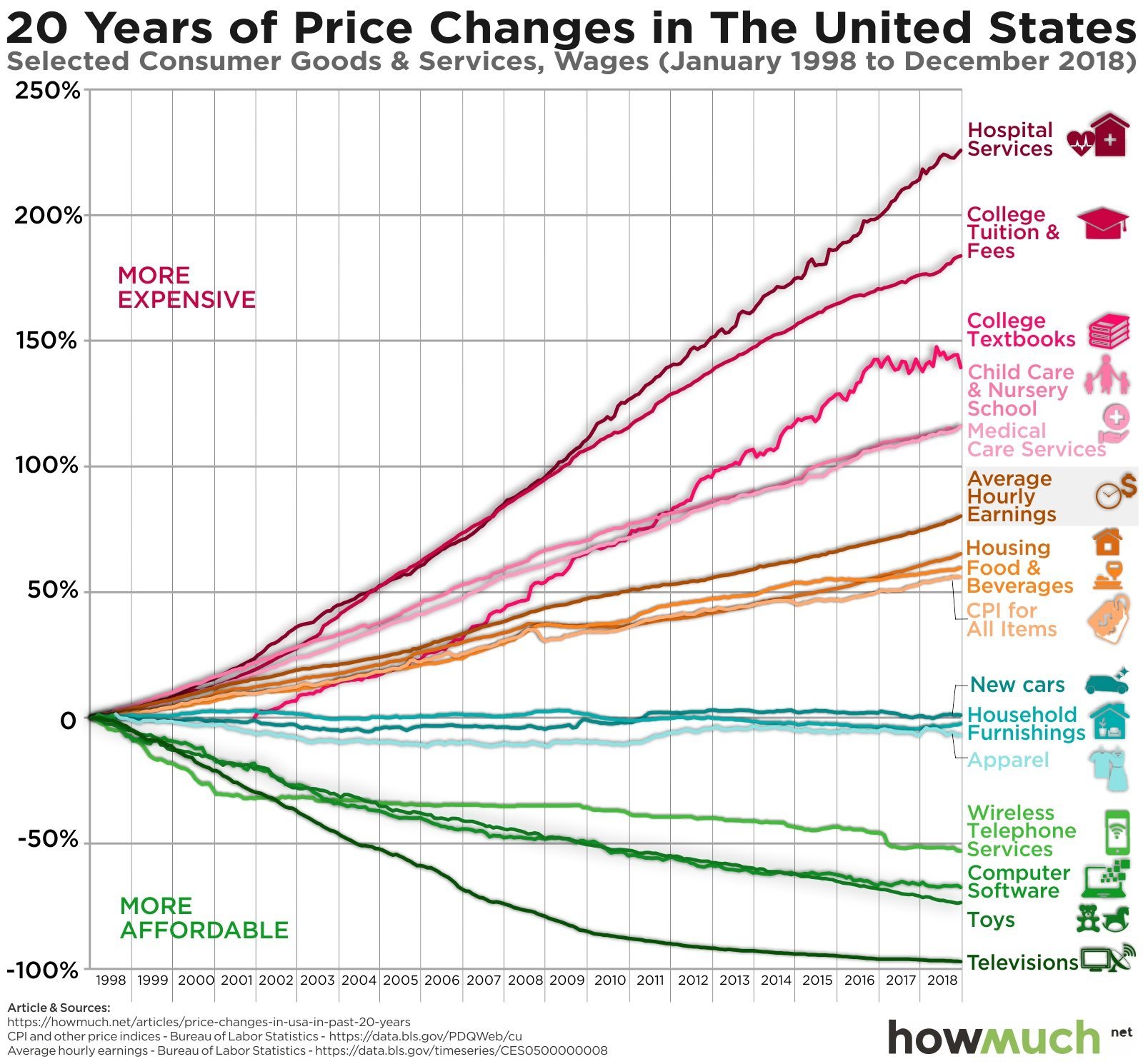

As a result, millions of pages of regulations now govern nearly every aspect of American business. While many of these rules are undoubtedly necessary, it’s reasonable to assume there’s significant overreach.

All of this reminds me of a talk Bill Gurley gave a while back on regulatory capture. Regulatory capture occurs when agencies tasked with regulating an industry become overly influenced by the interests of the organizations they regulate.

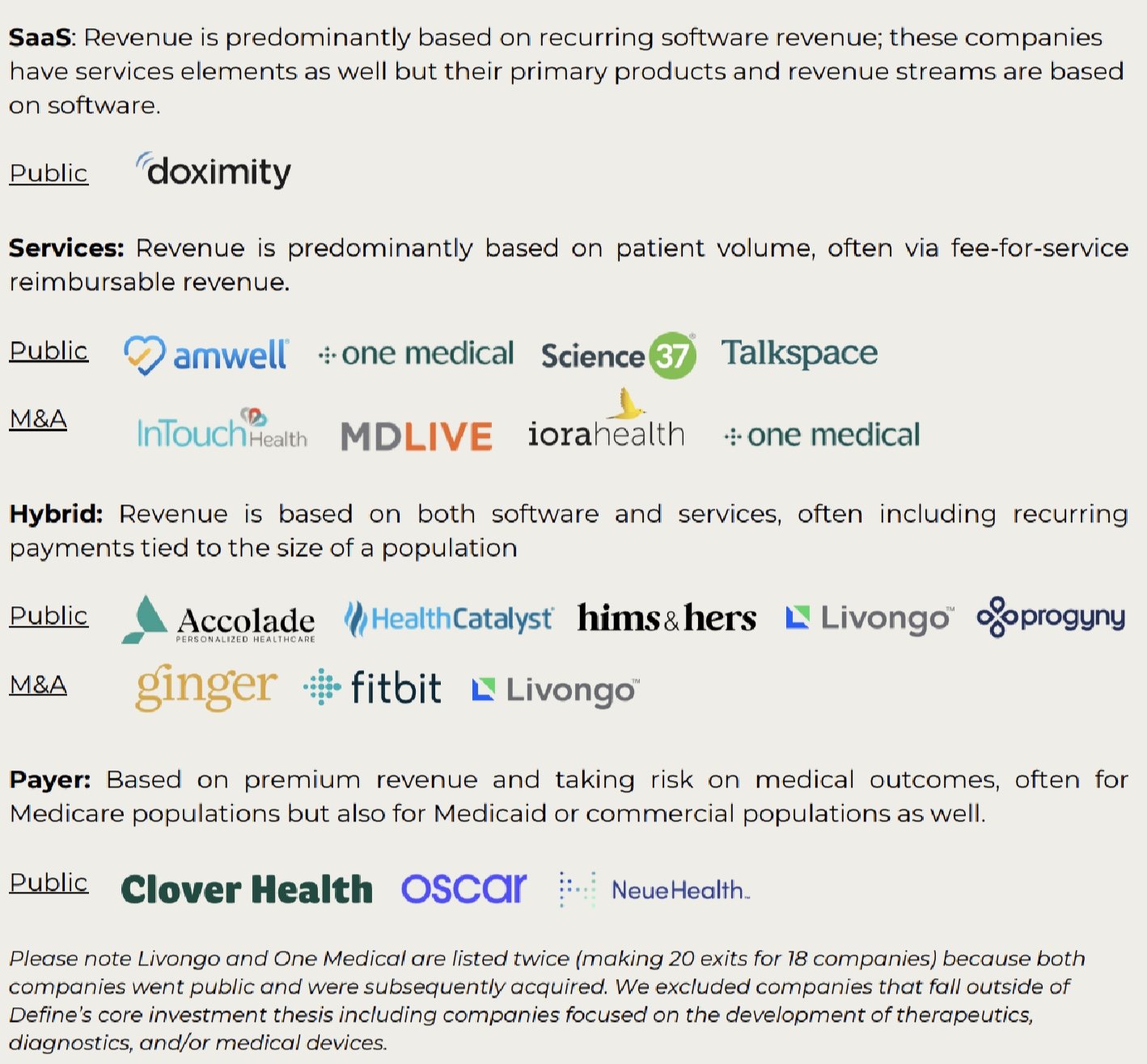

Gurley talked about a classic example of this in healthcare. Epic Systems, the healthcare software giant, benefited enormously from the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA’s HITECH Act incentivized healthcare providers to adopt electronic medical records (EMR) software. A new agency, the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC), now renamed to the Assistant Secretary for Technology Policy and Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ASTP/ONC), was established to administer this program.

ONC mandated payments of $44,000 per doctor to purchase EMR software and an additional $17,000 for demonstrating "Meaningful Use" — proof they were actively using it. Epic’s CEO played a pivotal role in designing the requirements for Meaningful Use, which aligned closely with Epic’s existing products. This created high barriers to entry, forcing smaller competitors out of the market or to incur major penalties for being out of compliance with the new regulations.

ONC has gone on to write more and more rules on top of the EHR standards for things like health IT certification, interoperability standards, and information blocking. If you work at a health tech startup, it’s more likely than not that these rules impact your company in some way.

Perhaps the best examples of regulatory capture came out of the Great Financial Crisis in 2008. Financial regulations, like Dodd-Frank, reinforced the dominance of the large incumbent banks. These rules imposed strict capital and compliance requirements, which big banks could absorb but smaller ones could not.

The result was that large institutions like JPMorgan Chase and Goldman Sachs emerged stronger than ever, making it difficult for smaller banks and new entrants to thrive.

Again, while many of these rules are valuable, many are not. And the overarching structure of the system generally favors large incumbents. This is true for two reasons:

1/ Lobbying Power: Large companies have the resources to influence Congress and federal agencies through lobbying and campaign donations. Many of them house large government affairs and public policy staffs in Washington.

2/ Established precedents: Policymakers often are reluctant to implement big changes to the way businesses operate and as a result design their programs and rules around the existing establishments.

If DOGE succeeds in reducing federal agency regulations, it would inherently challenge rules designed to protect the country’s largest companies that have benefited from the regulatory capture dynamic — ExxonMobil, Microsoft, Boeing, UnitedHealth, Walmart, etc.

This is a rather surprising effort to come out of a Republican administration that has typically supported big business, but it makes sense in the context of some of Trump’s other non-traditional decisions since winning the election. Take some of the comments he made when nominating RFK for Secretary of HHS:

“For too long, Americans have been crushed by the industrial food complex and drug companies who have engaged in deception, misinformation, and disinformation. HHS will play a big role in helping ensure that everybody will be protected from harmful chemicals, pollutants, pesticides, pharmaceutical products, and food additives.”

This statement sounds more like left-wing activism than traditional Republican rhetoric.

Back to the DOGE effort. No doubt the purpose of this effort is to reduce the cost of the federal government, but by unraveling many of the regulations that protect incumbents, this also starts to shift the balance of power back towards startups. Multiple VCs have talked about how these regulations have paralyzed the work of many startups, particularly in fintech, crypto, and AI. While Musk and Ramaswamy have run big businesses that have undoubtedly benefited from these regulations, they’re both founders and entrepreneurs as opposed to traditional, big company managers. Much of this effort feels like an indirect backlash against the “managerial revolution” where professional managers hold the primary power in organizations and economies as opposed to inventors, entrepreneurs, and founders. So, in some ways, DOGE isn’t just an effort to reduce the size of government; it’s also very much an effort to support a thriving and innovative startup ecosystem.

This won’t be easy. In fact, it might be impossible. There will be endless lawsuits, and large, powerful businesses with enormous lobbying budgets will scramble to protect the status quo.

But if it’s successful, DOGE has the potential to reduce the size of government and weaken the big established incumbents, creating more opportunities for startups to drive innovation. And it may realign some aspects of the American political party system. If it doesn’t succeed, it may simply underscore and reinforce how entrenched the existing system and structure have become.