There’s been quite a bit of news over the last several weeks of tech companies freezing hiring and laying off employees. Perhaps most notably, Meta (formerly Facebook) recently laid off 11,000 employees or 13% of its workforce. I thought I'd write a post about what tech companies are thinking about and the factors that are contributing to these unfortunate announcements. First, some history:

Until about a year ago, the stock market had been on a bull run for about 13 years. There are several reasons for this, but the primary reason was that, during this time, we had zero or near-zero interest rates. When interest rates are near zero, companies can borrow money almost for free, allowing them to invest heavily and grow, grow, grow. In addition, when interest rates are so low, money flows out of fixed-income investments and into riskier equity investments (the stock market). More money in equities means higher stock prices for public companies. Public company stock prices are a proxy for private company valuations, so private companies have experienced the same dynamics. This enabled companies to raise enormous amounts of money with little dilution for founders and shareholders. Due to classic supply and demand forces, more money in equities means that the same company with the same financial profile could be valued at 2 or 5, or 10 times what it would be worth in a less bullish market.

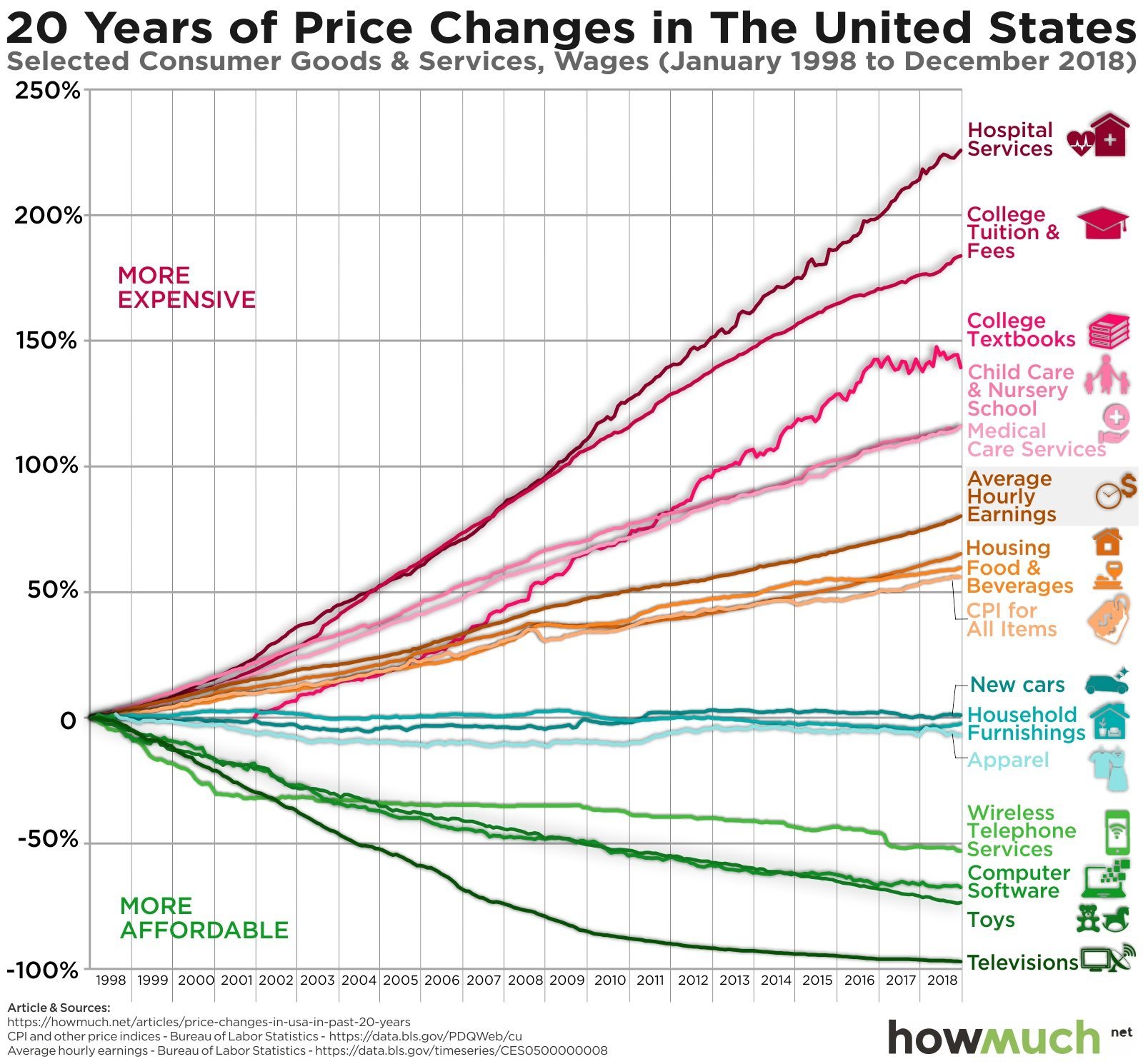

It was a great ride until COVID hit, and the economy stalled because people couldn't leave their homes and go to work and buy the goods and services they had been buying in the past. To get us through the crisis, the federal government rightly provided a massive economic stimulus to businesses and consumers by pushing more than $6 trillion into the economy. Again, more money in the system means higher prices for everything (including stocks). Due to COVID, we also saw major global supply chain issues and price spikes across nearly every category (again, the effects of supply and demand; reduced supply of products drives higher prices). Thankfully, the economy quickly recovered and Americans had surpluses of cash that they were anxious to go out and spend. And they did. As a result, we're now seeing historical levels of inflation. The inflation rate for the period ending in September was 8.2%; the average is closer to 3%.

This level of inflation is very dangerous. If prices increase faster than wages, it can literally topple the economy. And there have been lots of examples of this happening in the past. Luckily, the federal government can contract the money supply to slow inflation (less money in the system leads to lower prices). This has the effect of raising interest rates. And that's exactly what has happened; the federal funds rate sits at around 4%, the highest since 2008.

As a result, money has poured out of equities, particularly tech equities. The broader S&P 500 index is down about 15%, and the tech-focused NASDAQ is down about 30%. Tech companies get hit much harder in these cycles because they're investing in future growth and often carry a lot of debt. Because the profits from these investments won't be realized until further out in the future, increased interest rates discount the values of these future cash flows by an excessive amount (more on this soon).

An additional challenge is that as the Federal Reserve contracts the money supply and interest rates rise, it's not very predictable how quickly that will temper price inflation, so there's no way to know how long this drop in the markets and company valuations will persist. And there are reasons to believe it could get worse before it gets better.

For companies trying to navigate all of these changing conditions, their worlds have become much more difficult. Valuations are way down. As recently as 10 days ago, Facebook’s stock price hit $88, down from a peak of $378. Stock options granted to Facebook employees over the last 6 or 7 years are likely worthless.

Further, the cost of capital (both debt and equity) for companies has significantly increased. This hits technology companies, which, as I mentioned above, typically have higher levels of debt because they're investing in new growth, particularly hard. The cost of running these businesses becomes much more expensive because the cost of debt increases (increased interest expense). In addition, some of these debt covenants have requirements around growth and profitability that companies need to meet.

Moreover, and this is probably the most important part of what's going on that should be well understood, is that because tech companies are investing heavily in new growth, the profits from those investments won't be realized for several periods. And higher interest rates hit growth-oriented companies very hard because of the discount rate of future cash flows (more on that here). This is a very important economic concept that many in the tech ecosystem don't understand well enough. Said simply, a company is valued on its ability to generate future cash flows. And increased interest rates lead to a discount in the current value of these future cash flows far more than for companies that are profitable now. When interest rates are zero, there's no discount applied to future cash flows, so the market seeks high-growth companies that are making big, bold bets. When interest rates rise, investors look for companies that have profits now. Again, this is simply because of the discount applied to future cash flows.

Finally, and more broadly, businesses are seeing what's happening and are concerned that jobs will be lost, spending will slow, demand for their products will decrease, and a recession (two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth) might be on the horizon and bookings and revenue may decrease.

That's the situation tech companies find themselves in today. So how are they responding?

Well, it's important to remember that a company's primary purpose is to maximize shareholder value (for external investors and employees holding stock options). Management has a legal duty to its shareholders to operate in a way that maximizes the value of the company, regardless of the changing markets and the lack of predictability around when things will get better or worse. So in a market where near-term profits and cash flows are very highly valued, companies must pare back longer-term growth investments and find ways to cut costs to realize profits more quickly. And, because, typically, the vast majority of expenses of a tech company come from human capital (employees), the only material way to do this is to slow hiring or decrease headcount.

And this is exactly why we're seeing all of the news reports of tech companies freezing hiring and laying off employees.

Of course, some will criticize these companies for hiring too fast and overextending themselves, and voluntarily getting themselves into this situation by investing too heavily too fast. In many cases, this criticism is fair. But it's worth noting that, while cost reduction has rapidly become very important, in a bull market, growth is inversely and equally important. Facebook, as an example, is taking a lot of heat for overhiring engineers, but should they? I’m no expert on Facebook, but it’s an interesting thought exercise to think through for any company. Again, the job of a company is to maximize shareholder value. And when capital is cheap or free, the companies that invest heavily in growth will receive the highest valuations (again, refer back to the discount rate applied to future cash flows). At scale, had Facebook and the other tech giants chose not to make those hires, those individuals would've been unemployed during that period or would've received lower wages from other companies during that period, possibly displacing less talented engineers. If a company has viable ideas and areas to grow, and capital to invest in that growth is freely available, it must pursue that growth. It must maximize shareholder value. Companies with high growth potential have to play the game on the field. They have to pursue growth if they believe it's there. This is an unavoidable cycle that innovative companies are subject to. And individuals that work in the tech ecosystem will inevitably be the beneficiaries – and the victims – of these realities. Other industries experience far less dramatic highs and lows.

Of course, it should be noted that these highs and lows seriously impact people's lives. And I've been glad to see many companies (though not all) executing these cost reductions with humility, empathy, and generous severance packages.

With all of this said, inevitably, at some point, inflation will slow, interest rates will decrease, companies will invest in growth, companies will start hiring again, we'll be back in a bull market, and everything will seem great. In the meantime, it's important that all stakeholders that have chosen to work in and around tech understand and plan accordingly around the macroeconomic cycles that have a disproportionate effect on this industry.