Investing In Pure Health Tech

Define Ventures published an interesting report on venture-backed health tech investment performance titled Health Tech's Defining Decade. They point to a few relevant stats:

As of 2020, health tech makes up 10% of all venture funding.

In 2024, there was $18.6 billion in health tech venture investments.

10% of private unicorns (companies with valuations over $1 billion) are in health tech.

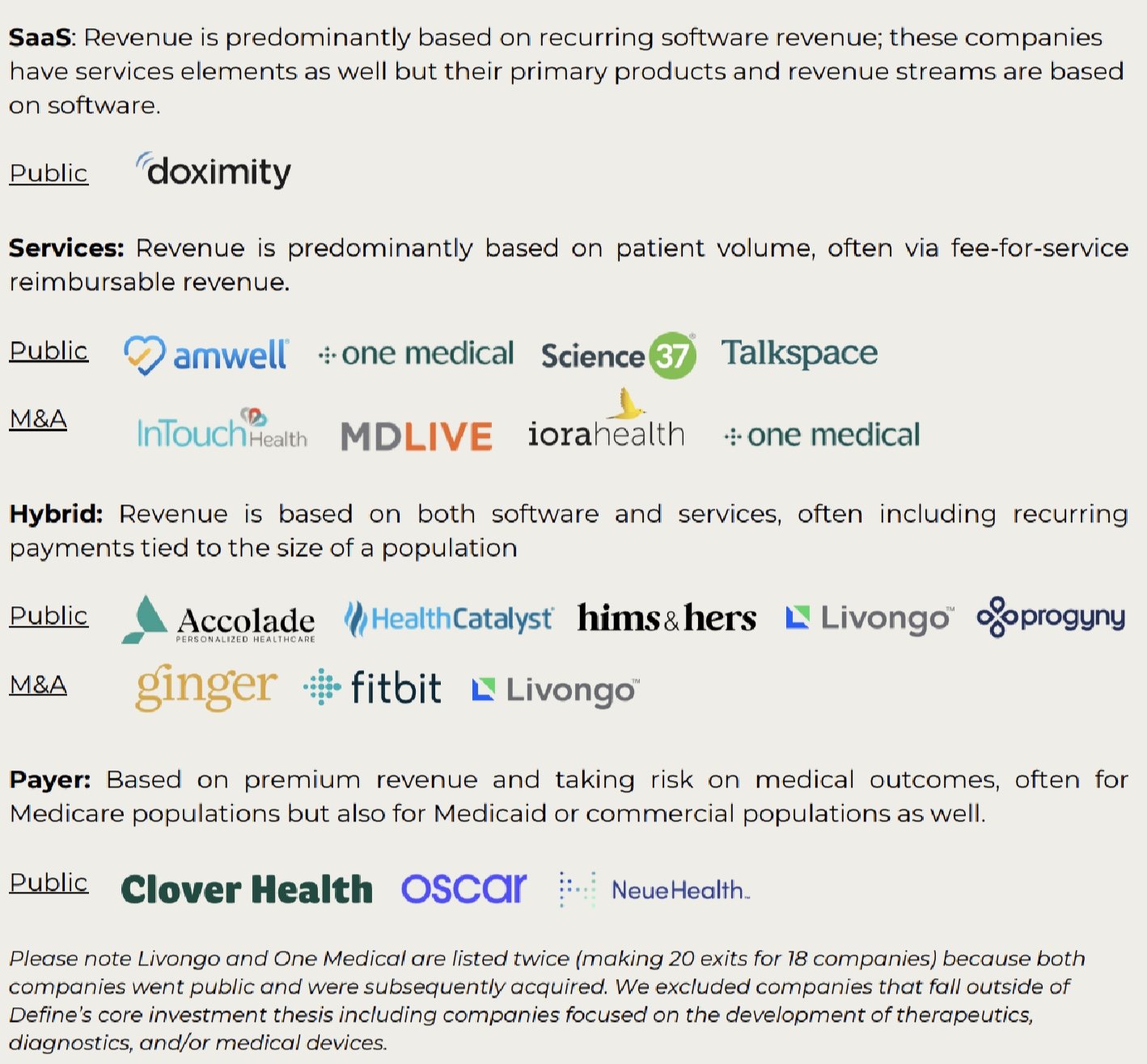

Since 2020, 18 health tech unicorns have exited (through IPO or M&A). See full list below.

I like the way they segmented the 18:

1/ SaaS (pure tech, software) - 1

2/ Services (serving patients) - 7

3/ Hybrid (mix of SaaS and service) - 7

4/ Payer - 3

This data speaks to the challenges of investing in pure software health tech companies or vertical SaaS in general.

With a couple of exceptions, the services and hybrid companies are mostly telehealth and traditional provider organizations with some tech that improves the patient or provider experience (I probably would've put Health Catalyst and Progyny more towards the SaaS, pure tech group and possibly Fitbit — while they're a hardware company, their profits are primarily software-based).

The payers are, well, payers with some tech to drive better outcomes.

The only pure SaaS company they list is Doximity, and while they are an incredible company, you shouldn't really think of them as a health tech company; they're an advertising platform for pharma companies. Again, they're a fantastic company and definitely support the healthcare ecosystem, but the vast majority of their revenue comes from the same budget pool as Instagram and Snapchat.

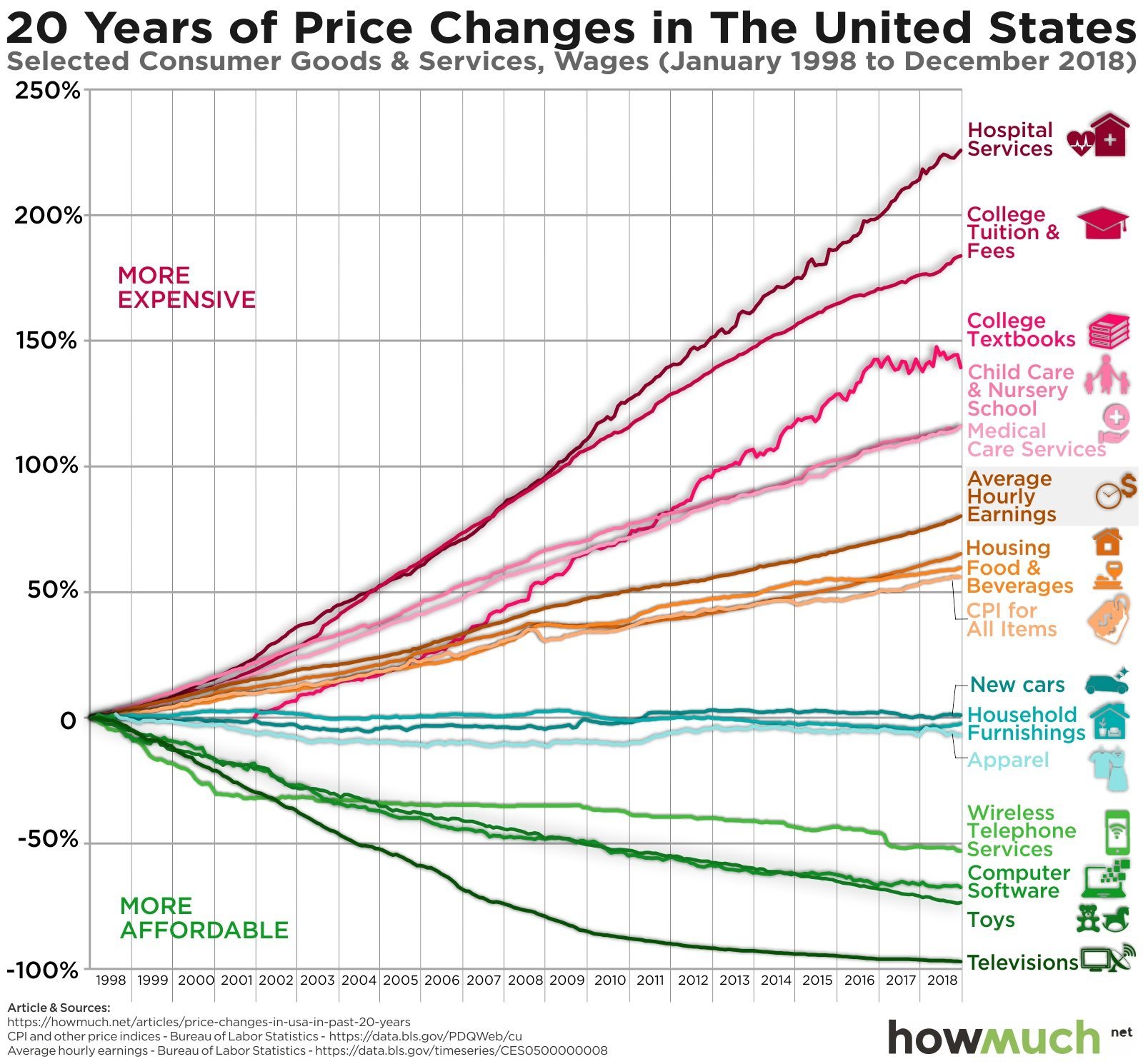

It's now become sort of a common trope for health tech companies to build a software product and grow really fast with nice high gross margin revenue only to find out they've run out of TAM (total addressable market) and need to pivot to lower margin services to continue to grow, and by services I don’t mean managed services or software consulting, I mean doing the actual work that their customers do. And that's consistent with this data. It's really hard for pure software companies in healthcare to get big. They can’t just provide software to their customers who do the work; they have to do the work, too. While people will talk about healthcare as a $4.5 trillion industry, healthcare IT represents just 4% of that, or about $180 billion. Most of the TAM has already been eaten up by EHRs, telehealth, analytics, and health information exchange. Further, the software infrastructure that large healthcare organizations use is dominated by several large horizontal software vendors — AWS, Snowflake, Salesforce, Symantec, Okta, etc.

So, the opportunity largely exists in either unseating the large incumbents in some form or in targeted areas, such as clinical/operational efficiency, patient experience/engagement, analytics, etc., but again, you're likely going to run into a TAM problem.

Of course, all of this brings us back to AI and how it will impact health tech and health tech investing, as that’s probably the best opportunity for more pure tech companies to achieve service-like valuations. And there are probably more questions about this topic that we haven't even thought of yet than the ones we have. My sense is we'll find that these products really impact margins more than TAM, but who knows? Regardless, as AI emerges in health IT, new frameworks will be required for how to think about these opportunities. I'll be thinking about that a lot and posting those thoughts here.